Programmed to Pop:

The Simple Secret to Finding Recurring Seasonality-Based Trade Ideas

By: Jim Fink

In this Special Report, you will discover...

- What is Stock Seasonality & Why I Use It

- Five Popular Investing Strategies That Seasonality Beats

- Seasonality Speed Bumps & How I Overcome Them

- The Top Three Ways to Profit From Seasonality

- Four Seasonality Secrets to Supercharge Your Portfolio

- 12 Picks with Strong Seasonality

- An "Over-the-Shoulder" Look at How to Find Seasonal Stocks and Buy Them

What Is Stock Seasonality & Why I Use It

The father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, famously said: “Price is what you pay; value is what you get.”

The key to investment success in the stock market is selecting stocks of companies with solid businesses that are selling at market prices below their intrinsic values.

But the stock market is inefficient, and stock prices can fluctuate below their fundamental values for short periods of time. Consequently, the best stock selection technique is a combination of long-term fundamental valuation analysis with shorter-term analyses of price patterns based on both calendar-based seasonality and technical chart reading.

Using stock seasonality involves quantifying seasonal price increases by examining a stock’s price history between a calendar start date and end date over a specific number of years. Then, invest in those stocks that have historically exhibited the most consistent one-way price direction during that time period.

Ten to twenty-five years is considered a reliable time frame. Because a business’ focus and competitive positioning can change significantly over time, a stock’s price action more than 25 years ago is probably less relevant to its current price action (perhaps stable blue-chip businesses like Coke and Procter & Gamble are exceptions).

Frequency of gains is the most important component of seasonality analysis. One wants to see a stock price increase during the calendar time period in at least 80% of the years being analyzed.

Seasonality refers to particular time frames during the calendar year when a company’s stock price is influenced by recurring forces that produce a consistent price direction – either bullish or bearish. Some stocks tend to go up consistently at certain times in the year.

For example, consumer-related stocks (e.g., food, drugs, beer, leisure, utilities, media, and retail) outperform the overall market between May 1st and October 31st and manufacturing and production stocks (e.g., consumer durables, chemicals, construction, mining, steel) outperform between November 1st and April 30th.

Seasonal tendencies can be based on weather events (temperature, precipitation, planting cycle), spending surges (holiday and back-to-school shopping, end of government fiscal years, tax refunds), new-product announcements at industry conferences, or financial events (quarterly earnings reports, dividend hikes, and regulatory approvals).

- Weather (heat, frost, flood, drought, harvesting)

- Portfolio window dressing (before quarterly and annual reports)

- Minimize Taxes (cash balance transfers between national jurisdictions and tax-loss selling in October for institutions and December for individuals)

- Positive emotions around holidays (July 4th, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas) and sporting events (Olympics, Super Bowl) leads to increased consumer spending and stock buying

- Preferred decision periods (Spending increases at end of calendar year because of “use it or lose it” budget balances and also increases at beginning of new calendar year when annual budgets are replenished).

- Extracted material consumption during spring homebuilding (lumber, copper), summer driving season (gasoline), new car models in autumn (steel), winter heating season (heating oil and coal), and gift-giving periods (gold, silver).

- Money flows (end-of-year salary bonuses, April tax payments)

- Industrial fairs (e.g., consumer electronics show, biotech conferences)

- Corporate events such as dividend hikes, regulatory approvals, and earnings surprises (e.g., Microsoft third-quarter earnings often a positive surprise)

Source: Seasonax February 1, 2023 webinar

The key is that the tendency is recurring and provides a high statistical probability that a stock price will continue to perform in the future in a manner consistent with previous price moves during a specific time of year.

Of course, there is no guarantee that future price patterns will mimic the past. and one can never completely discount the possibility of pure coincidence. Historical price patterns are unstable and could be temporary and coincidental, but in my experience knowing historical seasonality can – when combined with fundamental and technical analysis – improve the odds of a winning trade.

Although one can speculate, exactly what causes stock-specific seasonality is somewhat of a mystery. Maybe an individual company chooses to announce a dividend hike at a certain time each year that other companies don’t do, or a company has unique exposure in a foreign country that increases spending at a certain time of year when other countries don’t, or a company purchases its raw materials from a special supplier that cuts its prices at a certain time of year, etc.

As in physics, the behavior of objects is observable regardless of whether a good rationale for that behavior exists. The great physicist Niels Bohr once wrote:

In our description of nature, the purpose is not to disclose the real essence of the phenomena but only to track down, as far as possible, relations between the manifold aspects of our experience.

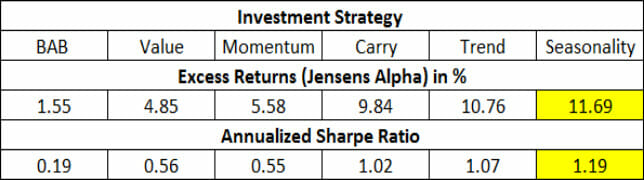

A recent academic study of very long-term multi-asset returns (stocks, bonds, commodities, and currencies), in the Journal of Financial Economics (December 2021) entitled “Global Factor Premiums” concluded that seasonality was one of the absolute best trade criteria for generating high returns on investment:

Five Popular Investing Strategies That Seasonality Beats

217-year study: Seasonality Outperforms Other Investment Factors in a Multi-Asset Portfolio

The Six Trade Criteria Put to the Test

In these markets the authors of the study compare the following investment strategies:

- BAB (betting against beta): low volatility investments are preferred.

- Value: the strategy is based on the idea that fundamentally cheap securities will generate better long-term returns than expensive ones.

- Momentum: in the “cross-sectional momentum” strategy, securities are purchased which have achieved the largest outperformance compared to the rest of the market over the past 3 to 12 months (the number of securities held is largely kept stable).

- Carry: In this strategy securities that offer large yields independent of their price performance in the form of dividend or interest payments are preferred.

- Trend: in contrast to the momentum strategy, the main criterion for comparison in this strategy is a security's own past performance: securities are purchased if they have performed well in the past (the number of securities held fluctuates).

- Seasonality: purchases of securities are timed to coincide with particularly favorable seasonal trends.

Source: Seasonax

Bottom line: seasonality-based trading not only makes sense, but it WORKS and has continued to work for more than 200 years.

This academic study in support of seasonality trading is not only fascinating, but it also confirms my personal trading experience. For several years before this academic study was released, I had been using seasonality religiously in both my personal stock trading and in my trading newsletters, Options for Income, Velocity Trader, and Jim Fink’s Inner Circle with eye-popping investment results featuring a 90%-plus win rate among all trade recommendations and a mixture of both double-digit and triple-digit-percentage returns.

Seasonality Speed Bumps & How I Overcame Them

I first started using seasonality in the 1990s when I got hooked reading The Stock Trader’s Almanac and Thackray’s Investment Guide, the bibles of seasonal investing.

The concept of seasonality is so attractive to me because it is based on what a stock price has actually done in the past, not based on groundless speculation about the future.

Back then, the main use of seasonality was to time entries into the stock market as a whole. That’s because the market had an amazing tendency to generate its price gain for the entire calendar year during the “best six months” between the end of October and the beginning of May and do virtually nothing between May and October (“sell in May and go away”).

Trading stock indices was not my forte, however. I was an equity analyst and value investor who focused on individual stocks, so I was much more interested in using individual stock seasonality to time my entry into individual stocks with strong business fundamentals.

The problem with utilizing individual stock seasonality back then was that there were no readily-available database sources to search for seasonal tendencies. I was forced to engage in extremely time-consuming trial and error, selecting some of my favorite stocks and calculating the rates of return between two calendar dates over a ten-year period and hoping that one of the stocks I was analyzing would have an extraordinary positive or negative seasonality over those ten years.

Trust me, after performing this laborious manual type of research on just a few stocks, you get tired, and it just gets worse if none of the stocks selected for analysis uncover an actionable pattern.

While such a laborious process may be tolerable for do-it-yourself investors, as a professional adviser with thousands of investors relying on me, I need something better, more efficient, and much quicker.

Fortunately, in the past 25 years computing power and databases have become much more sophisticated and comprehensive, which enables me to use expensive professional-grade software that automatically analyzes 500+ stocks simultaneously every time I recommend a trade, which is several times every week.

The seasonality software available today is amazing. All I need to do is input a start and end date and the software program instantaneously screens for those stocks that have risen at least 80% of the time during the specified time period over the past 10, 15, and 25 years. It also provides average and median returns per year and the Sharpe Ratio, which measures the average return per unit of risk.

I take this list and then do further screening based on my own chart-based technical indicators and my fundamental analysis of the company’s intrinsic value to find the best stock to trade.

The Top Three Ways To Profit From Seasonality

There are several ways one can participate in an anticipated stock move:

1. Buy the Stock

The easiest way is simply to buy the stock itself.

Besides this method’s inherent simplicity, the benefit of stock ownership is that one benefits from every single cent of stock movement in the forecasted direction and there is no time limit; if the stock doesn’t move as anticipated during the seasonally-strong period, one still owns the stock and can wait longer for the stock to move.

The disadvantage of stock ownership is that it is relatively expensive compared to other types of exposure and the rate of return is relatively low. The higher the investment cost, the lower the rate of return for a given dollar amount of profit. The magnitude of potential loss is also quite large. The higher the investment cost, the more money at risk.

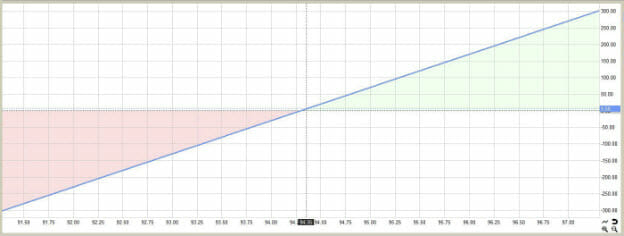

Profit/Loss From Buying a Stock

(Unlimited downside risk – down to a stock price of zero. Unlimited upside potential. Breakeven at current stock price)

2. Sell a Put Option

A second way that is safer on a per-share basis is to sell-to-open a put option at a strike price below the current market price of the stock.

Selling a put option generates cash up front that is credited to your account but obligates you to buy the stock at the option strike price if the stock moves against you and falls below the strike price at the option’s expiration date.

Since the option strike price is below the current stock price at the time of trade initiation, however, the net purchase price (and money at risk) is lower than it would have been from purchasing the stock directly in the open market.

For example, if a stock is trading at $95, you could sell-to-open a $90 put expiring two months out for a credit of $3 per share. If the put is assigned against you, that would mean purchasing the stock for a net cost of only $87 ($90 strike - $3 option premium sold), which is $8 cheaper than buying the stock outright for $95. Lower purchase price means lower risk. Furthermore, one can make maximum profit on the put trade even if the stock price falls all the way down to $90, whereas a stock purchase would lose $5 per share at $90. In fact, the put trade would not lose any money all the way down to a stock price of $87, whereas a stock purchase would lose money at any price point below $95.

The disadvantage of selling puts is that the potential profit is capped at the $3 per share credit received initially – even if the stock skyrockets by $50 to $145 per share, your profit is limited to $3. A second disadvantage is that a single option contract represents 100 shares of stock, so if the option is assigned against you, you would be required to purchase 100 shares of stock at a net cost of $87 per share, or $8,700 total. This cash outlay may be more than is optimal for a smaller account size, whereas stock can be purchased in any share size, from one share on up.

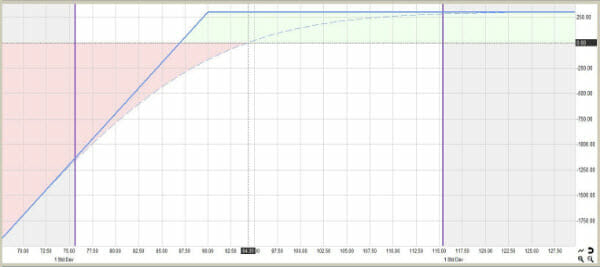

Profit/Loss From Selling An Out-Of-The-Money Put Option

Unlimited downside risk – down to a stock price of zero. Limited upside potential. Breakeven at $87, which is the $90 option strike price minus the $3 option premium received upfront for selling the put. (Solid line is profit/loss at expiration. Broken line is profit/loss at trade initiation.)

3. Buy a Call Option

A third way that is both easy and more profitable than stock ownership is buying a call option.

Buying a call option promises a higher return because it can offer nearly the same upside exposure to a stock’s price appreciation, but at a fraction of the cost.

The reason call options cost less is because you get to choose a strike price which is much higher than zero. To use beanstalk imagery, purchasing stock requires that you shell out money for the entire beanstalk, including the roots and trunk that simply tie up capital without providing any growth. In contrast, the call option buyer can bypass the roots and trunk altogether and focus only on the growth portion of the beanstalk by purchasing options with a strike mid-way up.

For example, if a stock was trading at $95, buying 100 shares of stock at $95 would cost $9,500 whereas buying a call option with a $90 strike expiring two months out could cost only $8 per share, or $800 per option contract (since each option represents 100 shares of stock). If the stock were to gain $10 per share, the stock owner would make a 10.5% profit ($10 stock profit / $95 stock purchase price), whereas the owner of the $90 call option with a 70% delta (i.e., the option gains 70 cents for every dollar gain in the underlying stock) could make an 87.5% profit ((70% x $10 stock gain) / $8 option purchase price), more than eight times as much.

Buying a call option doesn’t just help on the upside; it also helps on the downside because the lower investment cost of the call option acts like an insurance policy against a significant stock price decline. For example, if the company were to go bankrupt, the stock would drop to zero, the owner of 100 shares would lose his entire $9,500 investment whereas the call option owner would only lose $800.

The disadvantage of buying a call option is that its value includes a speculative component called “time value,” which increases the breakeven price of the trade above the current stock price.

As time passes, the option’s time-value component decays and detracts from your profit potential, but the decay is very slow when the expiration date is far away. There’s no way to buy an option without paying this speculative and decaying surcharge, but you can minimize its detrimental effects by either:

1. Purchasing a long-term option (i.e., LEAPS) that doesn’t expire for a year or more because time-value decay is not linear; decay quickens only near expiration, or

2. Choosing a strike price that is deep in-the-money (ITM) because the price of ITM options is almost entirely composed of non-decaying intrinsic value (I.e., the cash value available if the option is immediately exercised), with the decaying time-value component comprising only a very small portion of the total option price.

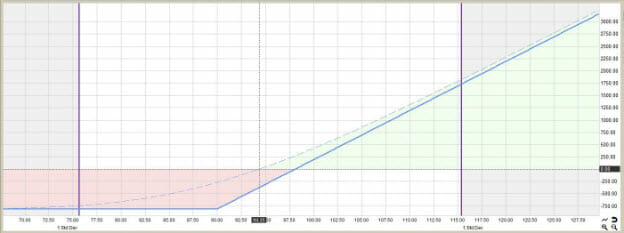

Profit/Loss From Buying An In-The-Money Call Option

Very limited downside risk equal to the cost of the call option. Unlimited upside potential. Breakeven at $98, which is the $90 option strike price plus the $8 option premium paid upfront. (Solid line is profit/loss at expiration. Broken line is profit/loss at trade initiation.)

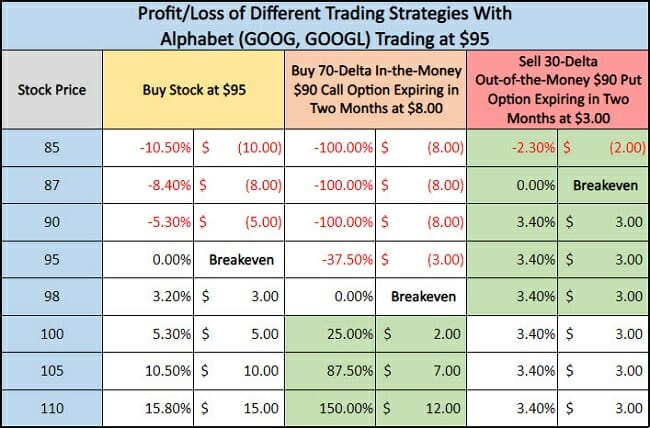

A summary of the risk/reward differences between the three trading strategies can be seen in the table below:

4. BONUS! Sell An Options Spread

There is actually a fourth trading strategy that is much better than any of the three trading strategies described above, but it involves a learning curve and requires some options knowledge to implement successfully.

Consequently, one must master the first three trading strategies before tackling this optimal fourth trading strategy. This fourth strategy, options spreads, is what I call the best investment strategy on the planet because it maximizes potential returns while minimizing costs.

I’ll tell you more about this later, so let’s get back to the benefits of seasonality analysis…

Four Seasonality Secrets to Supercharge Your Portfolio

When most people hear me use the term “stock seasonality,” they think I am only talking about frequency of gains (i.e., how many times in a specified past number of years that a stock has moved in a certain direction.)

Although a high frequency of gains (80% or higher) is obviously important, isolating stocks with a high frequency is only the first step to finding a trade with a high probability of success. Through my years of trading seasonality, there are at least four additional criteria necessary for a stock to qualify as a good seasonality trade that convinces me its high frequency of gains is not just a fluke or coincidence.

1. Magnitude of price gains

Magnitude is different from frequency. Magnitude is arguably just as important an attribute of seasonality for two reasons.

First, the average or median percentage price gain provides trading guidance on what a price target should be for the stock during the time period under study.

Second, a large average and median gain over many years provides reassurance that a high frequency of gains is not just a statistical coincidence, caused by tiny, random oscillations over and under the zero-percentage line. For example, a stock that has generated double-digit percentage rates of return in all of its up years is a better bet to continue generating positive returns in future time periods than a stock that has generated 0.1 percent rates of return in many of its up years.

Both average and median returns should be examined. A simple average return can be misleading – all it takes is one yearly return during the lookback period being analyzed that is an extreme deviation from the other years. For example, the Covid19-induced market crash in March 2020 caused almost all stocks to decline by huge percentages, had nothing to do with any company-specific seasonality, and yet it heavily skewed downward the average return of many stocks during the month of March over a ten-year lookback period. To minimize such “black swan” outlier events that are unlikely to be repeated, one should also look at the median return, which only looks at the single-year return that is in the middle of the series of returns. If there is a large discrepancy between the average and median returns, the median return is probably the better bet for forecasting the future.

2. Detrended stock price chart

Growth stocks early in their lifecycle tend to rise during all periods of the year, thus seasonally strong periods may be hidden by the fact that the stock is trending and all periods show price gains.

Despite what looks like a uniform upward price trend, the fact remains that even growth stocks have certain times of year where the company’s business experiences more tailwinds and performs relatively better.

One way to uncover the better seasonal periods is to compare the annualized return of the seasonal period under analysis to the annualized return of the remainder of the calendar year. I would rather bet on a stock that has an annualized seasonal return of 50% during the short time period being analyzed, which is 30% better than the 20% annualized return during the remainder of the calendar year, than bet on another stock that has a higher annualized seasonal return of 55%, but which is 10% worse than the 65% annualized return during the rest of the calendar year.

To make the relative price trends in stock charts during the calendar year more pronounced and easier to identify, one should use detrended charts, which eliminates the general uptrend of the stock and represents every time period as having the same starting price and ending price. By doing this, the uptrends and downtrends during the calendar year are much steeper and one can truly see which periods of the year have the strongest tailwinds and headwinds.

3. Volatility-Adjusted Returns

The main reason that stock returns are historically higher than investment-grade bond returns is that stocks carry more risk. Higher risk = higher return.

Bonds are safer investments that contractually guarantee a rate of return and their market prices consequently do not fluctuate much, which are very comforting attributes for an investor, which is why investor are willing to pay a higher price for such investments and accept a lower rate of return.

Price volatility is a symptom of investment uncertainty. Business conditions can constantly change, which can frequently change a company’s forecast of future cash flows and, consequently, change the stock’s valuation. The more uncertain a company’s business, the less confidence one should have that the price trends of the past will continue into the future. This is why calculating a stock’s average return per unit of risk (i.e., price volatility) is an important metric for evaluating the sustainability into the future of a seasonal price trend.

The industry standards for measuring risk-adjusted returns are the Sharpe Ratio and the Sortino Ratio. The Sharpe Ratio divides the stock’s rate of return (in excess of the risk-free Treasury bill rate) by its overall standard deviation, whereas the Sortino Ratio divides rate of return by only downside price volatility.

I prefer the Sortino Ratio because the only price volatility I’m worried about when betting a stock will rise is downside volatility – upside volatility is a good thing – so I don’t want a stock’s risk-adjusted return to be penalized for going up. In any event, for individual stocks, look for Sharpe Ratios of at least 0.75 and Sortino Ratios of at least 1.5.

4. Multiple Time Periods

The standard time period for measuring stock seasonality is ten years in length, which is enough time to determine a pattern is reliably repeating, but not so much time that the business prospects of the company may have changed so much that the earlier years’ returns included in the measurement are no longer representative of how the company is likely to perform now.

The flipside of this argument is that if a company’s business is not stable past ten years, then there may not be much reason to believe that the stock will perform in the next ten years the way it acted in the past ten years. Consequently, if I have to choose just one lookback period, then 10 years makes sense. But I feel most comfortable looking at multiple lookback periods and choosing those stocks that consistently exhibit extraordinary seasonality over 10-, 15-, and 25-year periods.

Consistency over multiple time periods gives me an extra boost of confidence that a stock’s seasonality is real and the company’s business dynamics are stable enough that the future is likely to look much like the past.

12 Picks With Strong Seasonality

I give subscribers to my financial publications dozens of new seasonality stock and options picks every week. Here are some tried and true ones for every month of the year, but they do require updated research every time just to make sure nothing has changed.

The returns below are from purchasing the stock. If you were to use any of the safe and simple options strategies I recommend, your returns would be much greater.

January: The famous “January Effect” is the idea that small caps outperform large caps in the month of January. But, savvy investors know that the “January Effect” actually starts in the middle of December. If you had bought the Russell 2000 ETF (IWM) on December 14 and sold it on January 12 of every year from 2001 to 2022, you would have earned an average return of 2.5% in less than a month and made a profit 86% of the time.

February: Novo Nordisk (NVO) is a Danish pharmaceutical company that seems like it’s “programmed” to pop every year on February 4th! If you held it for just 30 days every year for the past 20 years, you would have made an average return of 6.3% with an 85% win rate.

March: In the last 20 years, buying Adidas (ADDYY), the German “sneaker stock” on March 12th and holding it for six weeks would have been a winner 90% of the time! Your average return… 9.1%!

April: Houston-based oil company, Weatherford International (WFRD), seems to make a major move every April – it’s happened 24 of the last 27 years! And the average full-month return is a whopping 12%!

May: They say “sell in May”, but if you bought Vishay Intertechnology (VSH) instead, you’d have booked a profit 20 out of the last 27 years for an average gain of 6.8% that month.

June: 15 out of the last 19 years, pharmaceutical company Icon Plc (ICLR) has seen its share price jump an average of 9.3% in June!

July: One of the world’s largest biotech companies, Amgen (AMGN), has risen an average of 9.6% in 23 out of the last 27 Julys!

August: Traditionally a “soft month” for stocks, but not for this little-known energy company. Atmos Energy (ATO) has risen in August 20 times over the last 27 years.

September: Wall Street will tell you that September is the worst month on the calendar for stocks. But the Industrial Sector is the top-performing sector in September over the past five years. The average return is only 1.3%, but the broader market has fared much worse. Leading the charge are stocks like Albemarle (ALB), Caterpillar (CAT) and Deere (DE).

October: Microsoft (MSFT) is money in October. Buy on October 10th, sell on November 5th and 20 years of data is on your side to the average tune of 8.3%.

November: In the last 35 years this November stock strategy has worked 100% of the time! If the S&P 500 was down January through October, mutual funds will typically harvest tax losses by October 31 to offset their gains. Most of the stocks they sell then rise from November-January. In 2022/23, Starbucks (SBUX), Warner Brothers Discovery (WBD), and Digital Realty Trust (DLR) all followed this pattern.

December: Most people think retail stocks are the obvious play in December, but history shows a wildly different investment can spark year-end returns. The iShares Silver Trust ETF (SLV) has gone up an average of 9.2% from December 15 to February 23 over the past 16 years with a 13-3 winning record.

Additional Resources

1. VIDEO — "Programmed to Pop: How to Find & Buy Seasonal Stocks

Get an "over-the-shoulder" look at how to:

- Manually find seasonal stocks on your own

- Quickly find seasonal stocks in professional software like Seasonx

- Place 3 types of trades

-

- Buy a stock

- Sell a put option

- Buy a call option

2. Next month's seasonal stock trades...

UPDATE: We Found A Brand-New Seasonal Stock Trade!

We're Sending Out the Ticker Symbol & Trade Details Soon. Here's How to Get on the Distribution List

Click Here For Details

-